Incumbency as a reinforcing feedback loop – and Kim's loop-blindness

by Kim Kastens & Tim Shipley

A strong, enduring, widespread pattern

One powerful use for feedback loop thinking is to seek explanations for strong, enduring, widespread patterns in the real world. When a similar pattern of events shows up over and over again, at different times and places, and in different contexts, that can be a hint that there might be a feedback loop at work.

Kim's town of Acton, Massachusetts held its Town elections a few weeks ago. Voters made their way to the Junior High School gym to cast their votes for members of the Select Board, School Committee, Board of Water Commissioners, some other minor officials, and a couple of ballot questions.

In the contested races, every incumbent who ran for re-election was returned to office.

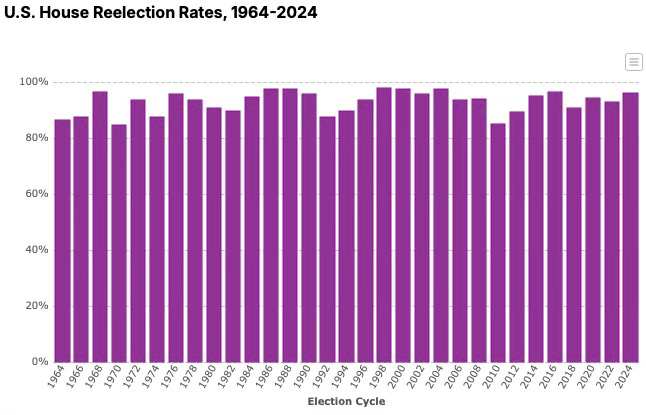

This is the norm across the United States. In most elections for the U.S. House of Representatives between 1964 and 2024, more than 90% of incumbents running for reelection won their race, according to Open Secrets (see graph below). This is a strong, enduring, widespread pattern.

In mulling over the Acton election results, and thinking about the nationwide pattern of election results, several potential causal factors come to mind. Let’s consider two of them: Incumbents typically have more name recognition than challengers. Incumbents may have had an opportunity to do nice things for their constituents, building good will among voters.

Each of these mechanisms has some explanatory power. But looking at this question through a feedback loop lens, we see that the factors that favor incumbency tend to compound over time, in a reinforcing feedback loops, like this:

Is this good or bad? It's obviously good for the incumbent and bad for the challenger, but is it good or bad for democracy? Perhaps some of both. Returning incumbents to office preserves organizational memory of how things got to be the way they are and why the organization does things the way they do. On the other hand, a system that favors incumbents resists the arrival of new perspectives, and disadvantages groups who arrived in town recently.

Reinforcing feedback loops tend to sow the seeds of their own demise, by activating balancing feedback loops that slow or disrupt the reinforcing loop. In the case of incumbency, as the years accumulate, voters may develop a desire for change (inner balancing loop in the diagram below). As the years accumulate, the incumbent is exposed to more opportunities to become embroiled in scandal or failure (outer balancing loop).

In a well-functioning democracy, no incumbent stays in office forever.

Loop blindness

Kim has been voting for fifty years. She first taught undergraduates about feedback loops 25 years ago, and has been researching how people think and learn about feedback loops for eight years. How can it be that only now, in 2025, she has awakened to the realization that incumbency is a reinforcing feedback loop?

We think that Kim's obliviousness is an example of a widespread phenomenon that Tim has termed "loop blindness."

Loop blindness is our label for when a person is familiar with a situation or phenomenon that is being strongly influenced by an underlying feedback loop – and yet they fail to recognize the presence of the loop. We haven't done any lab research on loop blindness (a great topic for an early career researcher, by the way), but we have informally observed numerous instances, in ourselves, in literature, in the media, and in everyday life. One of our goals in writing this substack is to help our readers overcome loop blindness.

We have some thoughts about why loop blindness occurs.

Feedback loops can't be seen, or heard, or smelled or tasted, or felt. Nor can they be sensed with sonar, radar, gas chromatograph, magnetometer, oscilloscope, Geiger counter, or any of the myriad of other devices that humans have invented to measure and map aspects of the world. Instead, the existence of a feedback loop has to be inferred.

Based on how things behave in the real world, and how that behavior changes over time, humans are capable of inferring that a feedback loop system of influences has been steering the behavior of the entities so as to create the observed patterns of behavior. But this is hard. Inference in general is hard. And it is particularly hard when the relevant observational evidence is incomplete, patchy, or noisy -- which is so often the case in real-world systems.

A surprising attribute of loop blindness is that, once pointed out, the loopiness of a system seems self-evident. It's one of those cases where once you see it, you can't unsee it.

Sources & Resources

For help understanding the diagrams in this substack, visit About causal loop diagrams.

About making inferences from observations: Tim wrote extensively about how humans think about events in the real world in Shipley, T. F. (2008). An Invitation to an Event. In T. F. Shipley & J. M. Zachs (Eds.), Understanding Events: From Perception to Action (pp. 3-30). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Based in part on that, Kim then wrote about how humans, including young children, can make inferences about events in the real world based on the traces that those events leave behind, in What precursor understandings underlie the ability to make meaning from data?, in the Earth & Mind blog. With geologist Basil Tikoff, Tim returned to the question of how humans make inferences from observations in a series of essays beginning with Shipley, T. F., & Tikoff, B. (2024), Lake Bonneville, Utah, and the role of the mind in the practice of geology.

About incumbency as a feedback loop: The thinking in this post is original, and Kim's loop blindness around elections is accurately reported. When we went looking in the literature, we found scholarly papers that analyzed one or more reasons why incumbents accrue an electoral advantage, such as here, here, here, and here. But we haven't yet come across an account that presents incumbency advantage as a reinforcing feedback loop (aka positive feedback loop.) Please tell us in the comments if you know of such a source. Incumbency advantage can be viewed as a special case of the "rich get richer" or "Matthew effect" feedback loop, which is well known and which we will be writing about in future posts.

Disclosure: Kim is a volunteer Associate Editor of the Acton Exchange, the independent non-profit hyperlocal online news source that covers Acton, MA, and thus was one of the authors of the linked article Results and reflections on Town elections by the Acton Exchange Team.